This is a series of posts where I will be geeking out on the philosophy, theology, and literary chops of one of the giants in Western culture and on my personal Mount Rushmore of influences: J.R.R. Tolkien.

J.R.R. Tolkien was famously critical of what he called "allegory." Tolkien saw allegory as fundamentally propagandistic. That is, the author is forcing down the reader's throat the meaning the writer wanted the reader to consume. He disliked Lewis' Narnia books for this reason, among others (he was also a stickler for mythological consistency, so having a dwarf (Norse) and a faun (Greek) in the same story made him intellectually vomit).

So, while I will demur with Tolkien (this is hard even to write, to be honest, given the high esteem I have for him) on the quality of Lewis' Narnia series, I think his critique is well-founded. Aslan is Jesus. It's basically impossible to read it otherwise.

Tolkien hated this style of writing fiction. But I think what he was actually reacting to wasn't so much allegory but rather propaganda.

Anyone can sit down and write a novel that tells a moral or a set of morals that they want readers to consume. Anyone can invent a story with a political or religious message they would like readers to adopt. God knows this is all Ayn Rand did in her novels.

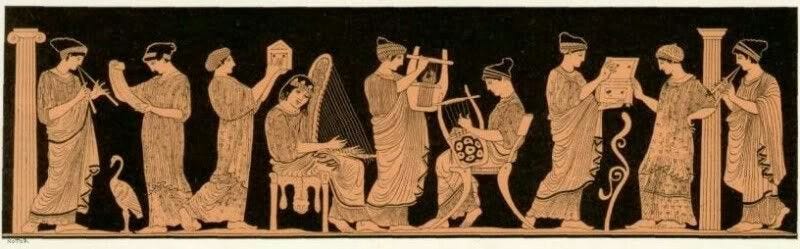

But good fiction isn’t like that. Homer starts his poems this way:

Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus, that brought countless ills upon the Achaea - The Iliad

Tell me, O muse, of that ingenious hero who travelled far and wide after he had sacked the famous town of Troy - The Odyssey

The idea here is that the story itself is being told by someone other than the one laying it down. It's a transcendental story being told through someone, not created by them. What Tolkien called "allegory," we may call propaganda. The difference between propaganda and good fiction is whether the author is speaking through the story or whether the reader is being lectured.

Good fiction does have a moral. It does have a purpose, a telos to the story. But the difference is whether you know the story has been crafted to force-feed you the message or whether the story is genuinely telling you a deeper truth the author is tapping into.

Tolkien's Lord of the Rings is resonant not just because it is telling a message but because it was telling a message without doing it intentionally.

[Lord of the Rings is] “a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision. That is why I have not put in, or have cut out practically all references to anything like 'religion,' to cults or practices, in the imaginary world. For the religious element is absorbed into the story and symbolism.”

Catch that and re-read the intros that Homer gave us. A Muse, in Greek mythology, was a goddess who gives inspiration for knowledge transferred through story, poetry, or mythology. Tolkien didn't set out to write a "Catholic" or religious work, but he ended up doing that. But it wasn't allegory, propaganda, or whatever. It was a story.

And the deepest, most resonant stories are those that have deep truths attached to them, but in ways you find unexpected, giving you new insights. Stories that aren't preaching to you, they're exploring with you.

J.R.R. Tolkien might have hated allegory, but I think he mainly hated propaganda. Propaganda is intentionally cynical. It's intentionally reductionistic and one-sided and, well, flat.

Tolkien backed into writing a very Christian story not because he set out to do this (he very much didn't), but because the Christian story is so universal, so compelling, so archetypal that it can’t help but be written once you know it, at least in some way.

It was an honest story. It was honest fiction, not propaganda. My next set of essays will be going through what all Tolkien's stories show us. Indulge me, if you will. I will, I promise, learn as much as you in writing about this.